Unreliable Narrator

I think I might be an unreliable narrator.

An unreliable narrator is one that misleads readers, whether it's intentional or accidental. To some degree, any narrator is unreliable insofar as you don't trust them. I had to read Turn of the Screw for a class. It tells the firsthand account of a governess (glorified babysitter) who sees ghosts as she tries to look after her charges (glorified babies). There's a widely agreed-upon suspicion among readers that the governess is unreliable because she's crazy—meaning there are in fact no ghosts and we can't trust her telling of events. The Catcher in the Rye is another example in which the first person narrator, Holden Caulfield, is unreliable and openly admits to lying: "I'm the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life. It's awful. If I'm on my way to the store to buy a magazine, even, and somebody asks me where I'm going, I'm liable to say I'm going to the opera. It's terrible."

I'm taking a page out of Holden's book and coming clean. I wrote a hitpiece on Netflix last month because I've sensed an anti-humanity vibe from Netflix for a long time. But just a few days after publishing that post, I loaded up on their stock mere hours before earnings. Netflix announced great results, I made a juicy 20%, and dumped the shares. I'm not really a degen trader-type. I don't ever make bets like this. That "investment" was inspired by whim and fancy—not my typical value-investing mindset. Once I finished rolling around in my money, I had a sobering thought: I dislike Netflix, yet I profited off of it. My next thought was "I'm an unreliable narrator" in my capacity as someone who writes on the internet. I'm the unkempt Holden; the hallucinating babysitter.

It might sound like I'm wallowing in my guilt. I'm not. I don't feel guilty because I think most people are unreliable narrators. I went to watch Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer) on the opening day. It was packed. I hate large crowds, and yet I had a pleasant time watching the movie. When the movie ended, I felt annoyed having heard President Truman berate Oppenheimer for whining about his role in making the atomic bomb. That part sort of took a battering ram to the whole movie for me—it's like reading a great book only to have it end with "...and it was all a dream".

Source: Jean-Jacques Salomon Science et Politique (1970) - * History in Quotations, Page 882"Oppenheimer when he went into Truman's Office with Dean Acheson said to the latter, wringing his hands: 'I have blood on my hands'. Truman later said to Acheson: 'Never bring that fucking cretin in here again. He didn't drop the bomb. I did. That kind of weepiness makes me sick.'

The nature of the capitalism is self-interest. My Netflix bet is just an instance of that nature. I'm less a steward of this blog than I am a steward of my self-interest. In other words, Oppenheimer is like the fiduciary to the readers of this blog and Truman is the degen-trader who made a killing. They're totally separate roles. I think at most Oppenheimer can be disappointed in Truman, but not feel entirely responsible for the whole ordeal. It's not a perfect analogy, but hey.

Speaking of unreliable narrators and Presidents, Donald Trump and his executive orders come to mind. In his first two weeks back in office, he's been stirring up wasps nests all around the world. He's threatened Canada's sovereignty, he's threatened to take back Panama's Canal, and he suggested beautifying Gaza's land. Besides the reduplication in the names of these places, there's not much accord to his plans. He ostensibly aims to put Americans first and improve their quality of life. But unless he allows us to stand inside his presidential lean-to, we really can't take his word for it. He's an unreliable narrator. Maybe he wants to achieve some big, notable wins and seal his legacy as a great President. Is that what motivated him to rename the Gulf of Mexico to Gulf of America? Maybe he's actually putting on a dog-and-pony show for posterity instead of making tangible improvements for people today. I know it's not exactly revelatory—this just in: we can't trust a politician—but it segues into the broader point about alpha.

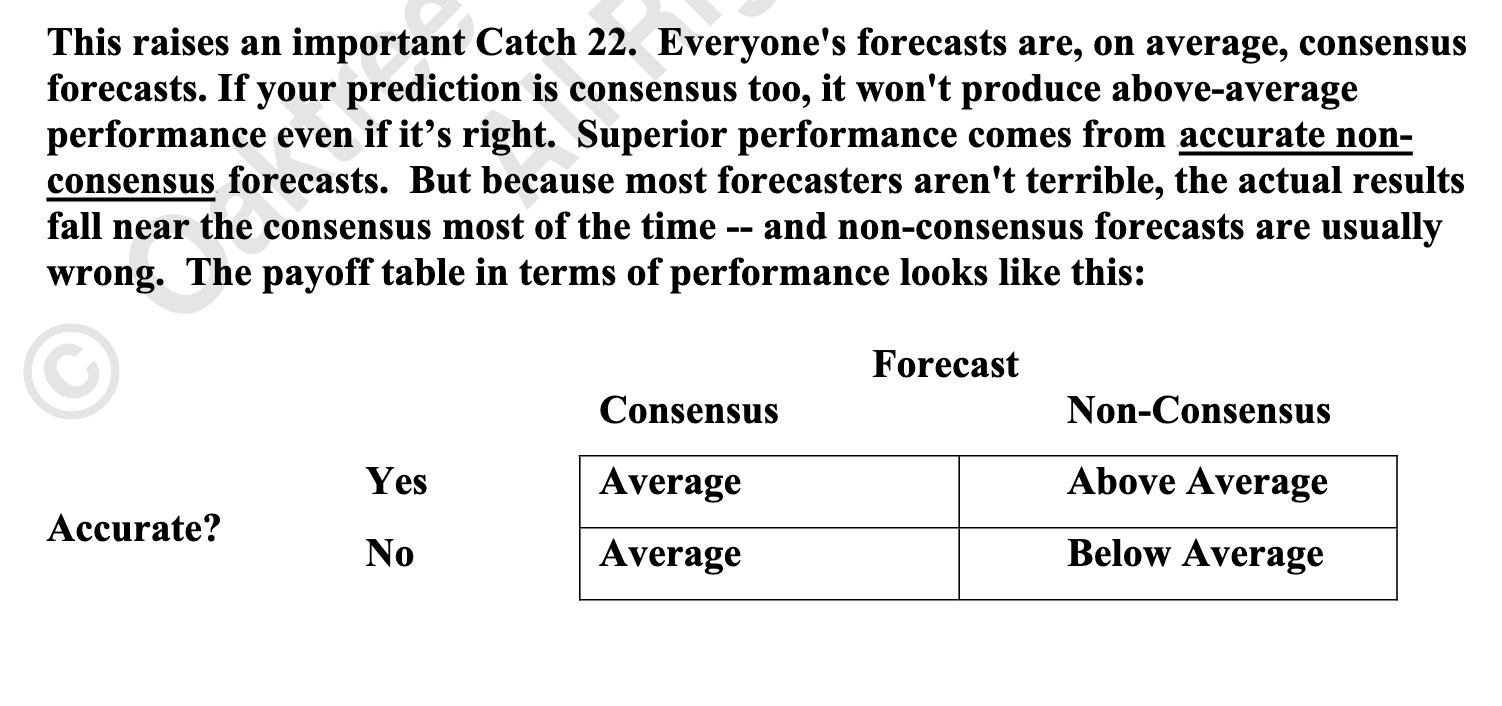

Everybody is looking for alpha. It's that same self interest at work. One of my favorite reads last year was Types of Memetic Information. I strongly suggest reading that blog, but in short the author classifies memetic information into three discrete categories: (1) memetic-invariant information remains constant in value regardless of how many people learn it; (2) memetic-cooperative information gets more valuable as more people learn it; (3) memetic-competitive information gets less valuable as more people learn it. In simpler terms, there are (1) facts, (2) open-secrets, and (3) regular secrets. That third category is the juiciest. It's what Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital alludes to in his famous 2x2 matrix on generating above average returns:

If you want a better forecast, you need memetic-competitive information—knowledge most people don't have. This is sometimes called insider trading and it's commonly frowned upon. But not all memetic-competitive information is illegal. When dealing with public information, the way you parse and combine information—fundamentally your pattern-matching capability or technology—is a form of memetic-competitive information. It's a secret. Somewhere in any winner's stack, you'll find secrets.

There are some special carve-outs where memetic-cooperative information (open-secrets) can be juicy. Greater fool theory is a strategy/scheme in which you buy an overvalued asset hoping you can sell it at higher price to someone else (i.e. some greater fool). This practice quite common in the crypto. For example, if you bought DOGE or SHIBA INU, you unwittingly applied GFT. By promoting a crypto, you can drive up the value for yourself.

Memetic-invariant information, or facts, rarely generate alpha. In rare cases, consensus becomes disoriented from the truth. Take online gambling: it's a fact that digital casinos are mathematically designed in favor of the house, yet millions of people still choose to gamble their way into devastating debt. By adhering to the fact, you avoid monetary loss and ipso facto generate alpha over those those millions of gamblers. In these rare cases, facts help you keep your bearings and you end up on top. But largely, facts don't generate alpha—secrets do.

People don't like sharing secrets.

If you believe that statement to be true, then everyone is an unreliable narrator. To the outside world, we're all just peddlers of barren, fruitless facts. We're all stewards of our own self-interest. If I found some obscure arbitrage opportunity in the stock market, I'd quietly exploit that infinite money glitch for as long as possible. I might share that tip with those closest to me, but not to the outside world. If you're reading a blog thinking the writer would share his most valuable insights, you're going to be misled.

If everyone is an unreliable narrator, what's the point of reading anybody's blog? Or reading a self-help book? Or listening to a business podcast? All the secrets worth exploiting must be discovered by oneself. Nobody, except for that rare, kind-hearted fool, is ever going to give you a valuable secret. No. You have to mine that information yourself. So, again, why read this blog, or any blog, book, or podcast? Speaking for myself, I like learning new things from interesting people. There's value in memetic-invariant information because it helps to orient yourself, and that puts you on the path to discovering juicy memetic-competitive information.

Why do fiction writers create unreliable narrators? Why not just write a straight-laced story? Unreliable narrators add depth to stories and make them far more interesting. They add flavor to a story, which would otherwise be bland and robotic. Stories explore the human condition; it would be unrealistic and unhuman for a narrator to lack all bias, have perfect mental health, and maintain zero self-interest.

We can modify that Holden Caulfield quotation from earlier to better understand every blogger, author, podcaster, etc you turn to for advice:

"I'm the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life. It's awful. If I'm on my way to [make a ton of alpha doing X], even, and somebody asks me where I'm going, I'm liable to say [Y looks attractive]. It's terrible."

- Your favorite blogger/author/podcaster